January 29, 2026

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- You may not need as much liquidity as you think

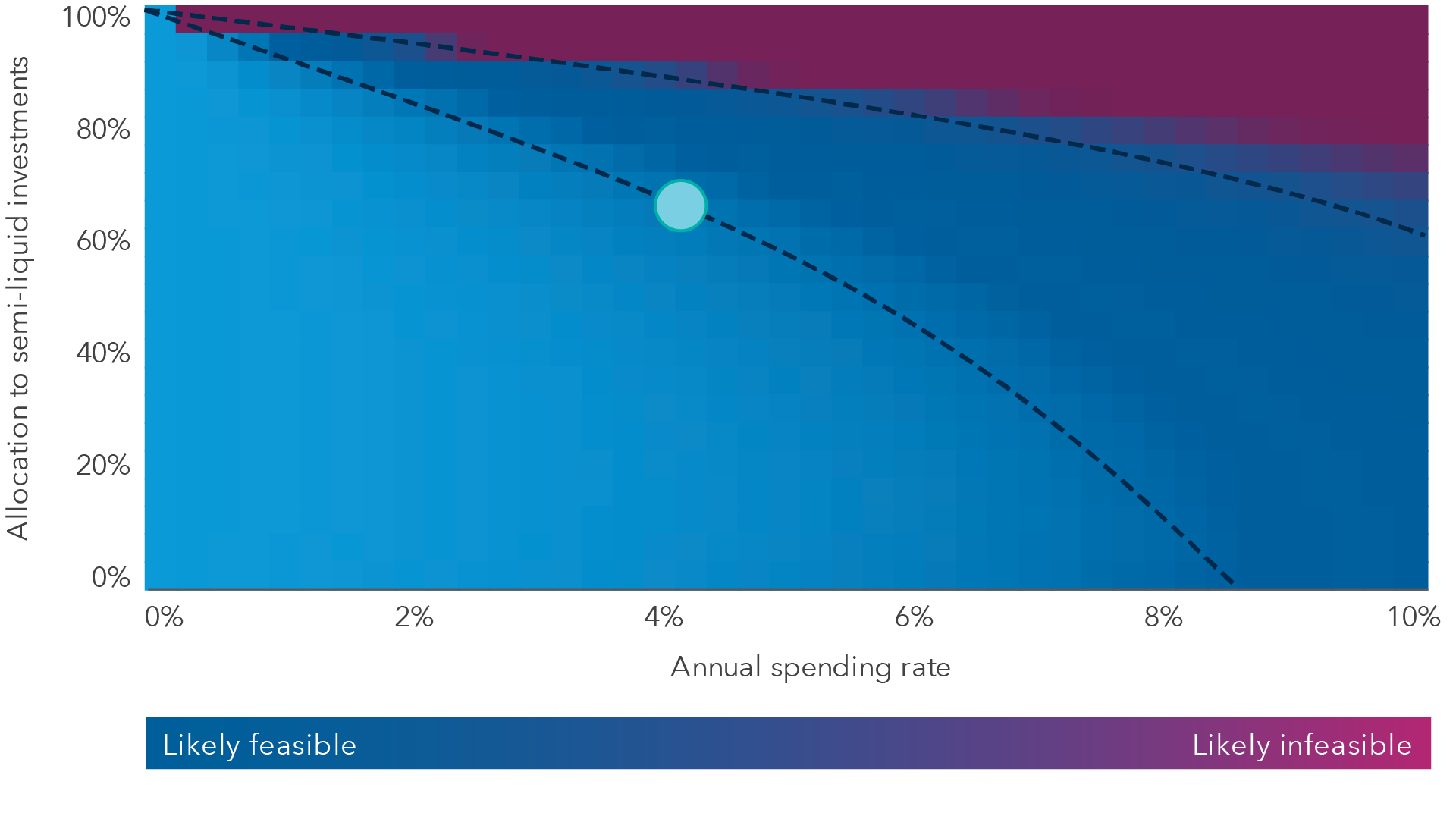

- Up to 67% of the average investor’s portfolio could be held in semi-liquid investments and still likely meet spending obligations

- Effectively managing liquidity presents potential growth opportunities and may help mitigate potential concentration risks

Investors may have greater opportunities to invest in funds or solutions with potentially higher returns than they might think. Our research suggests investors might overestimate the amount of readily accessible cash (known as “liquidity”) they need in their portfolios to pursue their financial goals. Investors should carefully consider the liquidity profile of their portfolios in discussions with their financial professionals, especially when allocating to semi-liquid funds.

What is liquidity?

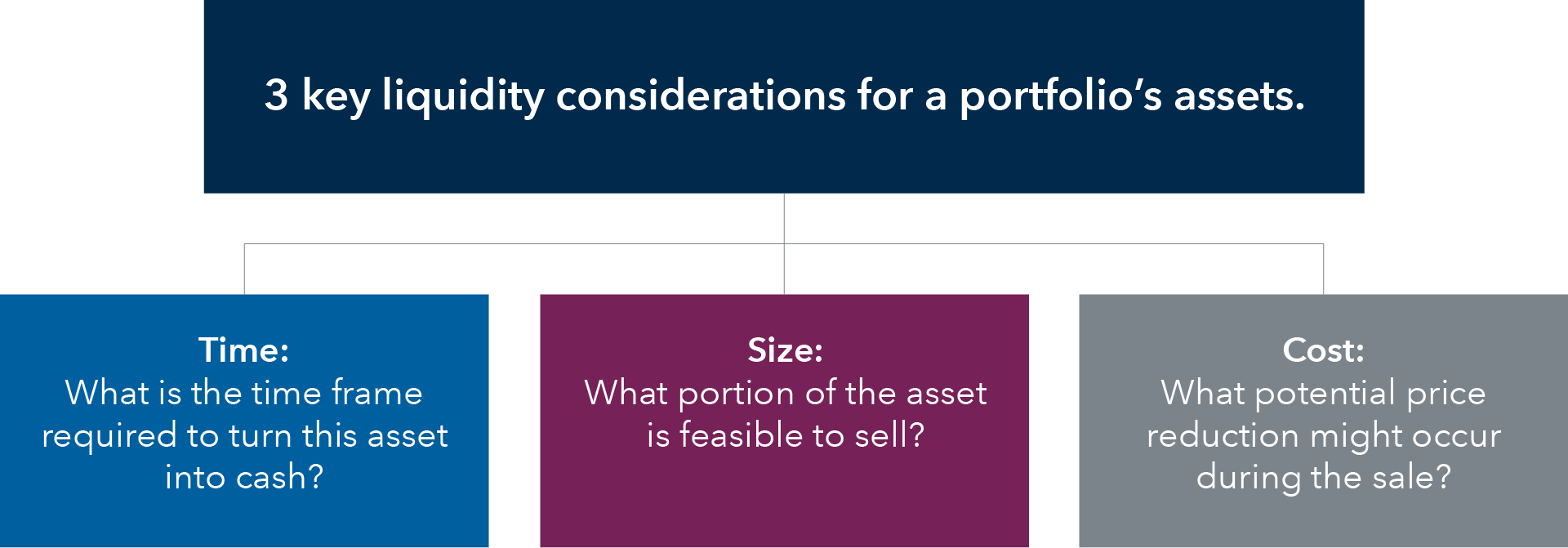

An asset’s liquidity can be estimated by asking three questions:

Certain types of assets, such as public equity (or stocks), can usually be sold quickly and in their entirety at market value. Assets such as those are considered highly liquid. On the other end of the spectrum, an investment property such as a physical office building would typically be considered illiquid. Real estate transactions can be lengthy and complex, and an effort to speed up the sale might necessitate accepting a bid that is less than the desired or fair market value.

Investors in illiquid assets often do so because they expect a potentially higher return, known as the illiquidity premium, although that is not the only possible benefit. Illiquid investments can also provide greater portfolio diversification, dampen perceived market volatility, and/or present an income generation opportunity, making them an important component of a cash management investment strategy.

Sitting in the middle, there are also semi-liquid investments such as interval funds. Interval funds can access private investments but provide limited quarterly liquidity.

Establishing a liquidity allocation budget

An investor's comfort with illiquidity may change over time and under different market conditions.

“We believe that by maintaining a public portfolio balance that is at least three times the projected annual spending requirements, investors may conservatively manage liquidity and meet their spending needs even during market stress.”

—Victoria Quach

That amount of cushion provides options for sourcing liquidity and allows room for market fluctuations.

Methodology: Simulated return data for global equities, U.S. fixed income, and private market assets that capture the mean, variance, skew, and excess kurtosis of each asset class from 6/30/2004-6/30/2025. Global equities are represented by MSCI ACWI Index and U.S. fixed income is represented by Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. Private market asset classes are composed of 45% MSCI Global Private Equity Closed-End Fund Index, 25% Cliffwater Direct Lending Index, 15% MSCI Global Private Real Estate ClosedEnd Fund Index, and 15% MSCI Global Private Infrastructure Closed-End Fund Index. Simulated 5000 paths, each over a 60-month horizon. The public portfolio rebalances on a quarterly frequency, and the private market portfolio rebalances on an annual frequency. Private market assets are assumed to have a 5% liquidation capacity. The spending amount is the spending rate as a percentage of the initial portfolio balance. The withdrawals are taken from public assets on a quarterly basis. The success rate is measured as the public portfolio balance being greater than or equal to three times the annual spending rate over a 60-month horizon. The illustrated feasibility range is the average across public and private portfolio allocations ranging from 0% to 100% in 5% increments.

For illustrative purposes only

Under our simulation conditions, the light blue point suggests that the “average” investor with a 4% spending rate could hold up to 67% in semi-liquid investments and reasonably expect to satisfy their spending needs.

That figure may be higher than some investors would expect, especially for investors who are newer to private markets investing. Private markets have historically been considered “alternatives,” but many of these markets have matured to such an extent that it may be worth thinking of them differently. Instead of a separate, pure alternatives allocation, there are ways to embed private assets into the core of a portfolio, as extensions of traditional equity and/or fixed income allocations.

Semi-liquid interval funds that combine public and private markets investments into a single integrated vehicle are one way to pursue potentially higher returns without fully compromising on portfolio liquidity. Reframing the way you think about private markets may help unlock new options for liquidity management.

Liquidity management

There are risks to how one approaches liquidity. Liquidating assets from one source overothers may change the proportion of exposures in a portfolio and can result in unintended over- or under-exposure to specific risks, such as market risk or credit risk.

Selling highly liquid, traditionally lower-risk assets (like cash or short-term, high-quality bonds) can reduce a portfolio's defensive components, leading to potentially greater portfolio risk. Excessive liquidation from short-term assets will also deplete readily available funds, potentially forcing future sales of less liquid assets under unfavorable market conditions.

On the other hand, selling illiquid and/or traditionally higher-risk assets (like equity and private credit) might reduce the portfolio's growth potential, especially if that asset is sold before it’s had the chance to realize its full potential value.

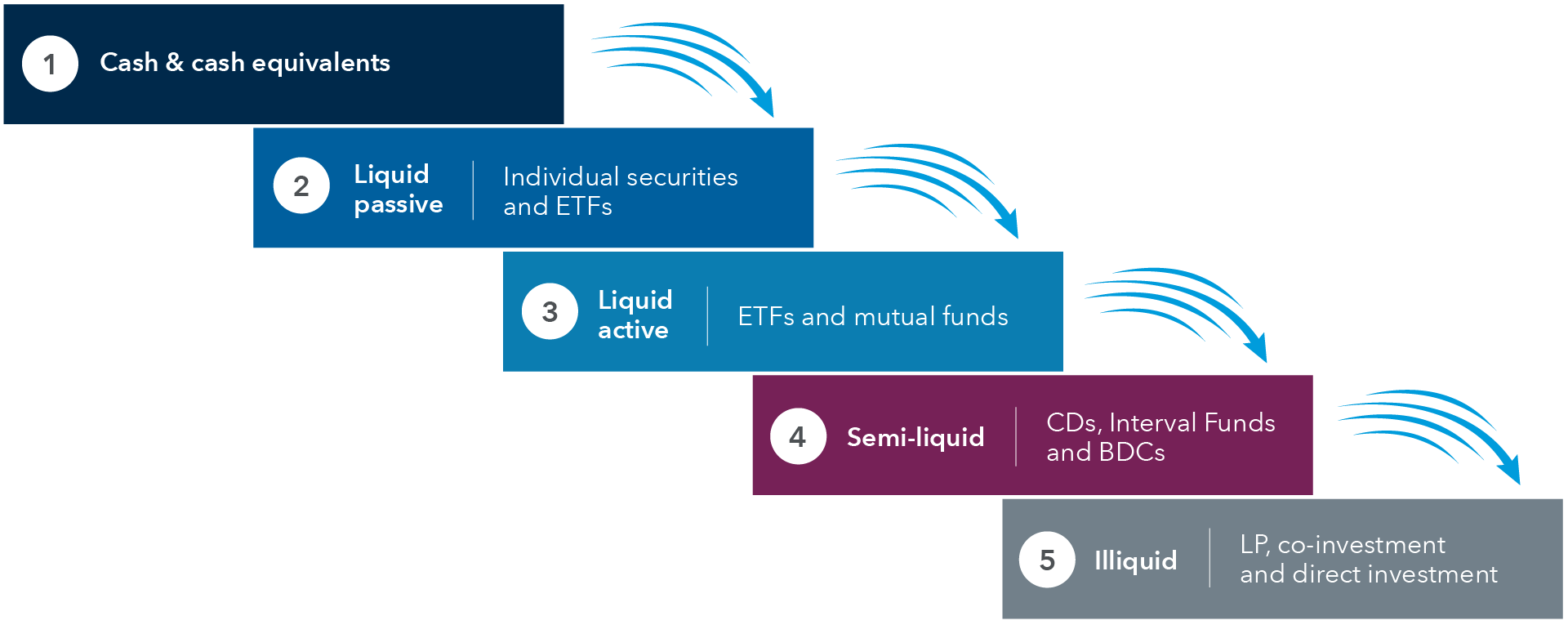

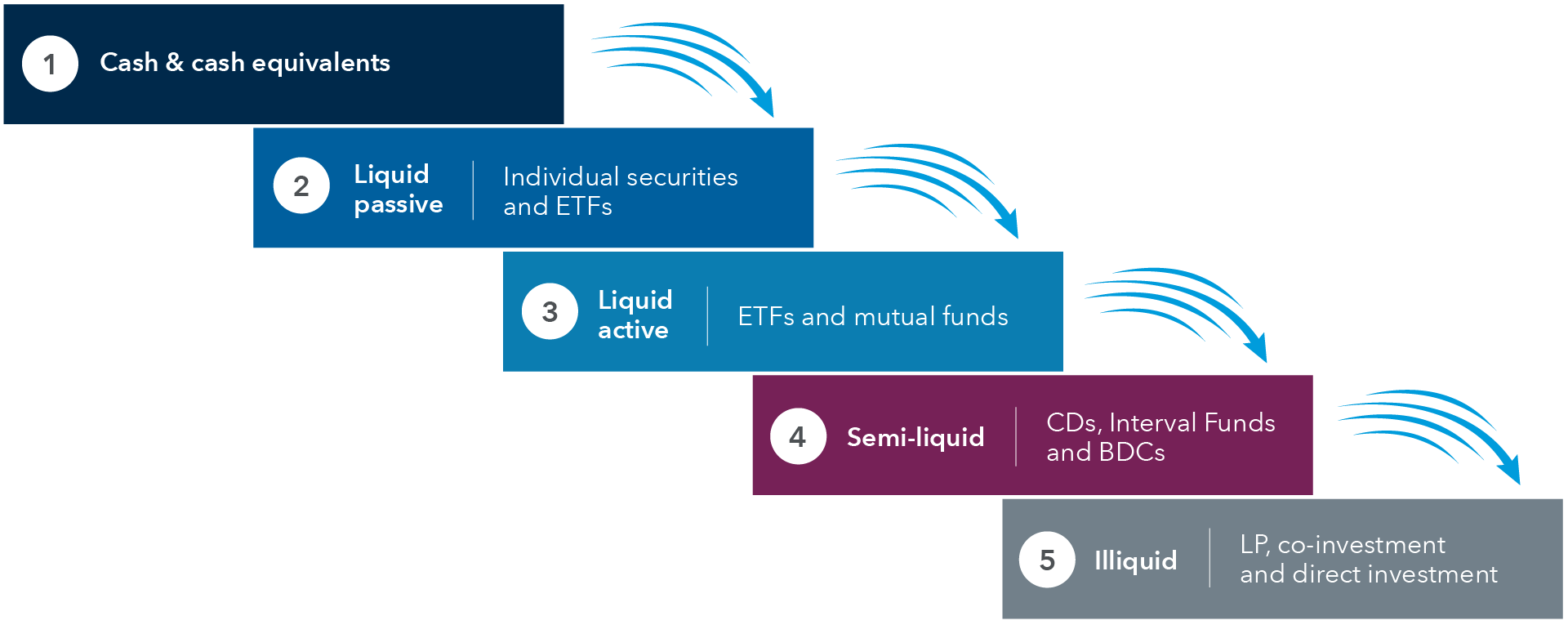

It’s important to have a framework for navigating the spectrum of liquidity and aligning an investment’s liquidity profile to broader portfolio objectives and investment horizons. It may be helpful to think of a “liquidity waterfall.”

For illustrative purposes only. The structural liquidity of passive and active ETFs and mutual funds does not differ.

At the top of the waterfall, cash and cash equivalents provide immediate access to capital, making them ideal for meeting short-term liabilities or maintaining emergency reserves. Next in line are liquid passive assets like U.S. Treasuries or broad-based ETFs, such as ones tracking the S&P 500. By drawing from passive assets before active ones, you keep the potential for excess returns that active management brings in the portfolio. Finally, illiquid assets such as private credit or private equity should be seen as a liquidity source of last resort, due to the difficulties in selling them quickly.

For an investor who is considering allocating to illiquid or semi-liquid assets, it is important they discuss with their financial professional not only their risk tolerance and time horizon, but also any spending commitments they might have, especially in the near future. Understanding each investor’s unique circumstance involves knowing when funds will be needed, the expected spending rate and the subsequent portfolio’s capacity for risk. The actual need for liquidity should be a central part of comprehensive financial planning.