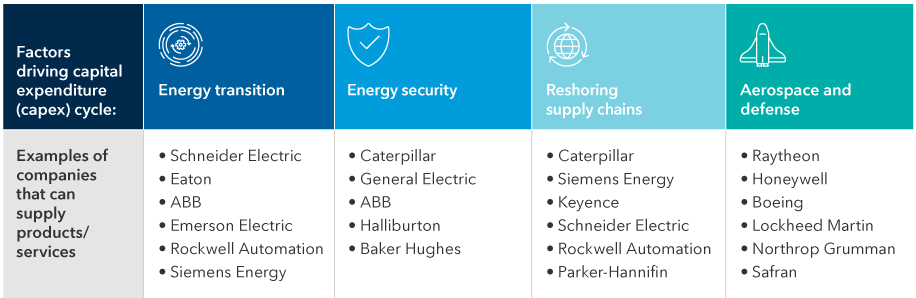

The pandemic served as a wake-up call, as government shutdowns resulted in snarled supply chains that lasted well beyond the reopening of economies. Companies began to recognize the importance of more local suppliers as well as the wisdom of sacrificing maximum efficiency in favor of some redundancy in case of future breakdowns.

“Manufacturers realized that they needed more resilience, which is to say visibility into their supply chain, the flexibility to change over the types of production and remote monitoring,” Pardasani says. “Resilience also means backup plans in case something happens to the facility, a supplier or employees.”

In January, Korean solar panel company Hanwha Q CELLS disclosed plans to construct a $2.5 billion manufacturing complex in Georgia. And last December Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) disclosed plans to spend $12 billion to build a second chip factory in Arizona, scheduled to be in operation in 2024. TSMC is also building a semiconductor plant in Japan and has plans to make infrastructure investments in Europe.

Intel is building a research facility near Plateau de Saclay, France. The company had disclosed that France will become its European headquarters for high performance computing and artificial intelligence design. And Europe itself has recently opened LNG terminals on Germany’s north coast to receive imports from the U.S. and elsewhere.

As companies build new factories, they seek to offset some of those costs by adopting the latest and most efficient technology. For example, Japanese industrial company Keyence develops automation sensors, vision systems and measuring instruments for a range of manufacturing operations, and SMC produces pneumatic and electric automation equipment.

In the U.S., Rockwell Automation provides controls, software and automation equipment for a wide range of factories, including many automakers. “Rockwell has a particular presence in solar energy,” Pardasani says. “So they’re seeking to do for solar what they’ve already done for the auto industry.”