Chart in Focus

Markets & Economy

Is the U.S. dollar at a turning point? A sharp decline late last year has left many wondering if the greenback’s decade-long bull run is coming to an end.

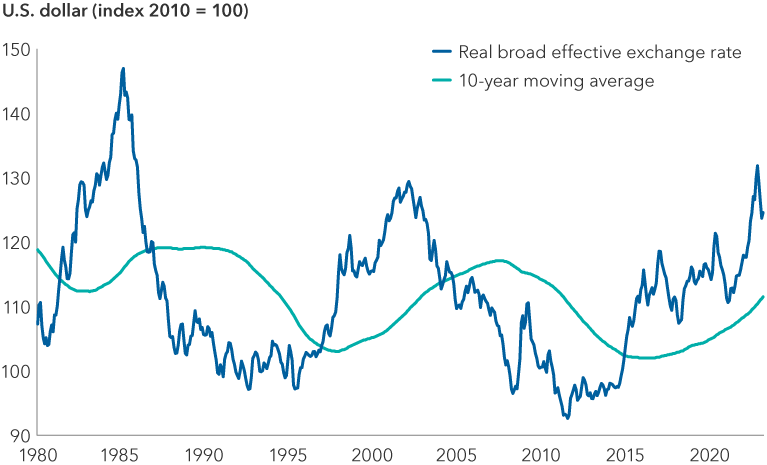

A continuing downward trend would be welcome news for investors in international bonds and equities, whose total returns have been eroded by currency translation effects. And, in many ways, a correction is overdue. From its trough in 2011 to the recent peak in late 2022, the U.S. dollar rose 45% against J.P. Morgan's inflation-adjusted broad-based basket of developed and emerging market currencies. This has left it overvalued against most major and emerging markets (EM) currencies on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.

But these metrics suggest the dollar has been overvalued for quite some time, and valuation alone has not been enough to bring it back down. For a longer term decline to set in, there must be one or more catalysts. These are a few we are watching that could influence the direction of the dollar.

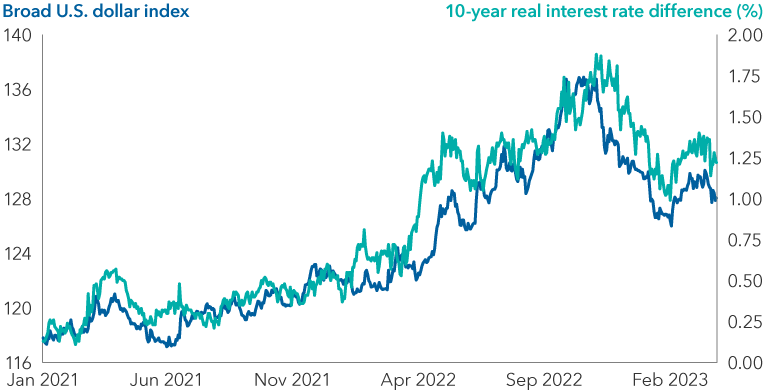

1. Interest rate differential between the U.S. and Europe is narrowing

In the pre-COVID era, interest rates were low in all the major economies. Nevertheless, rates in the U.S. were higher than those in Europe, Japan and other developed markets. That was the primary factor propelling the dollar higher against most currencies. Investors around the world could earn higher interest rates while enjoying safe haven status. High forward interest rates also meant investors could buy bonds denominated in the euro and the yen, hedge them into U.S. dollars and earn a higher interest rate (carry).

The U.S. dollar is significantly above long-term average

Sources: Capital Group, J.P. Morgan. Data as of March 31, 2023. The real broad effective exchange rate measures the value of the U.S. dollar against a group of developed and emerging market currencies and adjusts for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). CPI is a commonly used measure of inflation that measures the average change over time in the prices paid by consumers for a basket of goods and services.

Several factors supported comparatively higher U.S. nominal and real interest rates: a hawkish Federal Reserve more determined to raise interest rates than the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BOE) or the Bank of Japan (BOJ), plus a strong and productive U.S. economy and higher inflation.

Now this picture is changing, especially relative to the euro. The swift collapse of three U.S. regional banks — SVB Financial, Signature Bank and Silvergate Bank — has led bond markets to lower expectations for both the terminal federal funds rate and Treasuries across the yield curve. Meanwhile, European bond yields could still move higher as the ECB stays on its rate-hiking path should inflation pressures persist.

It’s also been interesting to see that in the most recent episode of market volatility attributable to the banking sector, the dollar has hovered in a range of 92 to 94 cents to the euro. Swift action by the Federal Reserve to provide dollar liquidity via swap lines with other central banks provided support to the U.S. currency. (Swap lines are agreements between two central banks to exchange currencies. They allow a central bank to obtain foreign currency from the central bank that issues it and distribute it to commercial banks in their country.)

Overall we expect the differential between U.S. interest rates and those in Europe to narrow. This could remove some support for the dollar, which was trading around 92 cents to the euro as of March 31.

One reason for a potential narrowing: The ECB started hiking later than the Fed. After raising rates by 250 basis points (bps) last year, the ECB probably has further to go if it wants to bring inflation closer to its 2% target. Meanwhile, the Fed may be closer to pausing, or potentially cutting rates, than it had anticipated before the U.S. bank failures. Markets expect the rate gap to decrease by about 90 bps (from around 1.8% to 0.9%) by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, the BOE increased its policy rate by nearly 425 bps, putting U.K. nominal and real interest rates closer to the U.S. than either the ECB or the BOJ. Its actions helped lift the pound 15% against the U.S. dollar after U.K. government turmoil forced it to an all-time low in September 2022. What happens next to the sterling will likely depend more on potential further rate hikes than any other variable. At this point, the BOE seems less aggressive than the ECB or the Fed.

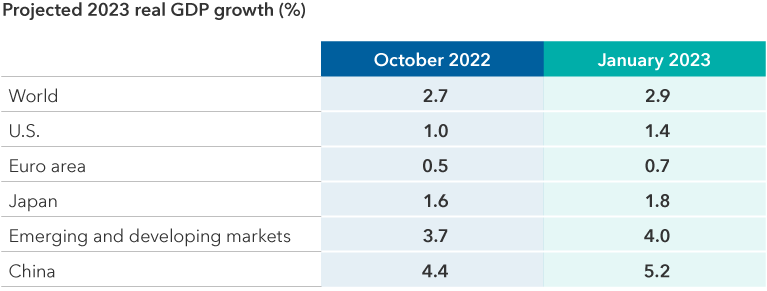

2. Economic outlook across various markets and countries is improving

Growth prospects for China, Europe, Japan and emerging markets are looking brighter. Just a few months ago, China’s economy was hampered by the government’s zero-COVID policy, Europe was facing a potential winter energy crisis, Japan’s economy unexpectedly contracted in the third quarter and the risk of a global recession loomed over emerging markets.

China’s sooner-than-expected economic reopening improves 2023 growth prospects for the country as well as the rest of the global economy. After years of being trapped at home, many Chinese consumers have the savings and demand to fuel spending. Measures of consumer activity and manufacturing already show signs of improvement. China's government has been providing billions of dollars to shore up its ailing property market and also appears closer to wrapping up reforms for private sector technology companies.

2023 global growth outlook improves

Source: International Monetary Fund. Data as of January 2023.

European economic data show reduced risks of a deep recession, as forward-looking manufacturing and service sector Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) data point to better conditions. The sharp reversal in energy prices due to a warm winter is helping manufacturers and consumers.

Japan’s economy is also proving to be resilient. Consumer demand is holding up despite higher inflation. The service sector shows signs of improving, the labor market remains tight and manufacturing should get support from China’s recovery. Corporate investment may also be improving.

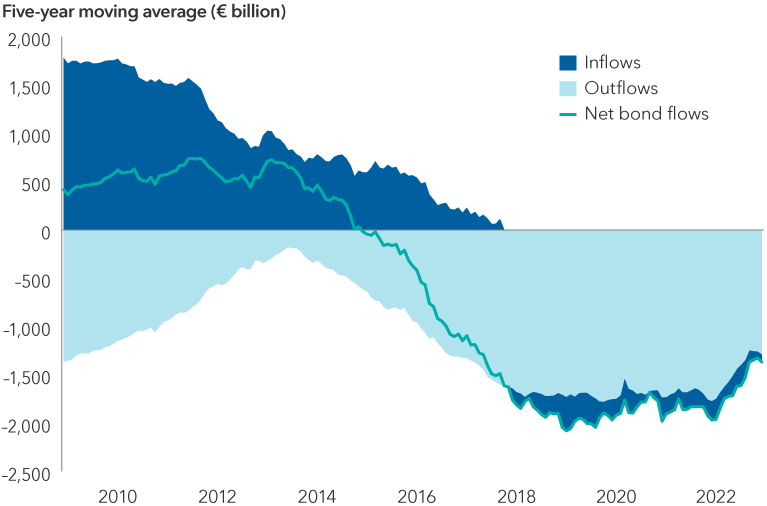

3. Portfolio flows may begin to support the euro

In recent years the ECB’s negative interest rate policy and quantitative easing measures kept foreign investors away, but those policies look set to change. If policy rates between the ECB and the Fed narrow as expected, another driver of euro weakness and dollar support is likely to dissipate.

Europeans have been buying far more foreign bonds than international investors have been buying into Europe. As a result, the five-year moving average for net bond flows in Europe has been negative since 2014. While it’s hard to pinpoint, a majority of outflows likely went to the U.S., given the market’s liquidity and size.

Sources: Capital Group, Haver Analytics. Data as of December 31, 2022. Outflows = eurozone bond purchases abroad. Inflows = foreign purchases of eurozone bonds. Data start date is December 2008.

Meanwhile, the carry advantage between the U.S. and the eurozone is becoming less compelling. When the Fed aggressively hiked rates before the ECB, an attractive carry opportunity arose. Even after the cost of hedging currency risk, using euro-denominated assets to buy dollar assets was attractive. However, that hedged trade is becoming less profitable, which should reduce euro selling and flows into the dollar.

4. A rising Japanese yen: possible but fragile

The Bank of Japan’s extreme monetary policies have long kept the yen from appreciating against the dollar. The BOJ has implemented yield curve control (YCC) — pegging 10-year government bond yields near zero rate — as well as negative interest rates and massive quantitative easing to pump inflation closer to its 2% target.

Signs of stronger inflation may finally be here. Japan’s core consumer price index, which excludes fresh food, rose 4.2% year over year in January. And some companies appear to be complying with BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s call for wage increases above the rate of inflation.

If the BOJ believes inflation can stay around 2%, it will have cover to gradually unwind some of its policies. In a surprise move last December, the central bank loosened its YCC policy slightly, and we expect it to make a similar announcement this year.

Allowing 10-year yields to rise should support the yen. Trading around ¥133 to the dollar, it is among the most undervalued currencies, according to our currency analyst Jens Søndergaard’s valuation model. Even slightly higher domestic rates would incrementally reduce Japanese dollar demand.

In addition, an increase in Japanese interest rates and potential volatility from BOJ policy uncertainty could make carry trades more expensive. However, the interest rate differential between the yen and the dollar also depends on Fed action. If stubborn inflation pressures force the Fed to raise rates beyond current expectations, the yen could remain depressed.

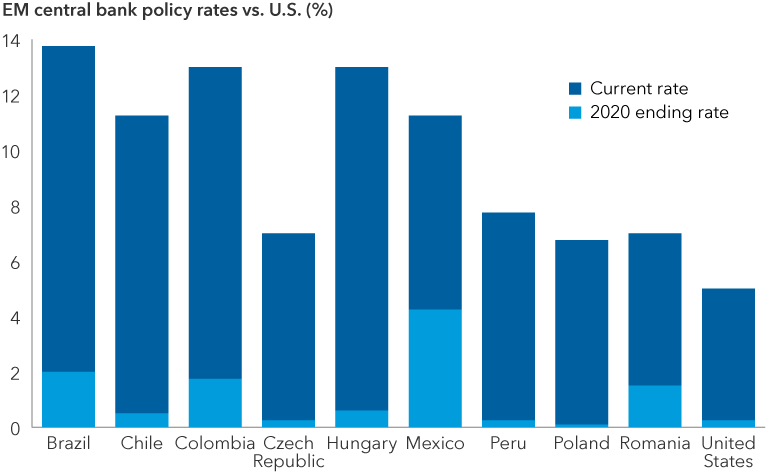

5. Emerging markets are further along the curve on monetary policy

When inflation picked up in 2021, EM central banks responded quickly and aggressively. Latin American central banks led the charge. Brazil’s central bank started hiking rates in March 2021 and took its policy rate from 2.00% to the current 13.75%. Eastern European central banks picked up their pace after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And the spike in energy prices last year led some Asian central banks to increase rates.

EM central banks raised rates aggressively

Source: Bloomberg. Data as of March 31, 2023.

High interest rates in nominal and real terms have been supportive of EM currencies, which have attracted investors looking for income. The Brazilian real and Mexican peso were among the few currencies that strengthened against the U.S. dollar last year. In addition to attractive nominal and real yields, macroeconomic conditions have improved. The tilt toward more positive fundamentals is likely to continue overriding political risk concerns in those countries for now.

In many Asian economies, a combination of attractive interest rates, improving growth prospects and strong macroeconomic fundamentals are supportive of currencies.

China’s economic reopening should broadly boost Asian growth. In Southeast Asia, we believe the Thai baht is becoming more compelling as increased tourism drives up economic growth rates and foreign flows. A rebound in commodity exports from Indonesia to China may benefit the Indonesian rupiah.

The Korean won also appears to be undervalued. Exports to China will likely rebound, and Korea’s financial position could get stronger. As a large energy importer, Korea faced a severe headwind from last year’s jump in prices — hurting businesses and consumers — but the drag should lessen significantly this year.

Further support to EM currencies could come when the Fed stops raising rates. In that case, EM central banks may find it easier to lower their policy rates, especially if inflation keeps easing or growth softens. That said, the rate differential between many emerging markets and the U.S. will likely remain attractive, providing a potential tailwind to EM currencies.

What are the risks to this view?

If the global economy weakens more than expected as the full impact of monetary tightening makes its way through the system, the U.S. dollar could find support given its status as a safe haven currency. This would likely delay a repricing of the dollar to its fair value.

A long-term dollar decline also requires Europe, Japan, China and other emerging markets to show substantial improvement in economic fundamentals, including gains in productivity and economic reforms favoring free enterprise and capital investments. Over the past decade, the U.S. economy has gained its edge from technology and health care innovations as well as an economic incentive system that supports entrepreneurship.

While it is early, we do see modest signs of change. In Europe, Italy has laid out a post-pandemic recovery and resilience plan. If properly executed, it would be meaningful, as Italy has been a European growth headwind for many years. Germany is breaking from its long-held stance of fiscal conservatism and is willing to provide a boost to consumers and industries even if it means running larger deficits along with other EU members. And while increased fiscal spending in Europe should stimulate growth, it’s unclear how it will affect inflation and the ECB’s efforts.

Other conditions in Europe are also looking more favorable. Fears of a peripheral debt crisis or a eurozone breakup have decreased. The eurozone’s responses to Brexit, the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine appear to have helped reassure investors that the region is a safer place to invest than it was a decade ago.

Japan is starting on a slow path of normalizing its monetary policy while providing some support to the economy. Meanwhile, many of the large emerging markets have shown monetary discipline by keeping rates high in the face of inflation and tempering fiscal stimulus. But a structural and sustained uplift in financial assets, including currencies, will depend on economic reforms varying from labor and land acquisition laws to intellectual property protection and joint venture policies.

The market indexes are unmanaged and, therefore, have no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

The use of derivatives involves a variety of risks, which may be different from, or greater than, the risks associated with investing in traditional cash securities, such as stocks and bonds.

Eurozone Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is a measure of business activity compared to the previous month, based on a survey of around 5,000 companies based in the euro area manufacturing and service sectors.

BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Bloomberg’s licensors approves or endorses this material, or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

This report, and any product, index or fund referred to herein, is not sponsored, endorsed or promoted in any way by J.P. Morgan or any of its affiliates who provide no warranties whatsoever, express or implied, and shall have no liability to any prospective investor, in connection with this report. J.P. Morgan disclaimer: https://www.jpmm.com/research/disclosures

Don't miss our latest insights.

Our latest insights

-

-

Municipal Bonds

-

Global Equities

-

Long-Term Investing

-

Federal Reserve

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

Chart in Focus

-

Municipal Bonds

-

Global Equities

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Andrew Cormack

Andrew Cormack

Philip Chitty

Philip Chitty

Tom Reithinger

Tom Reithinger

Harry Phinney

Harry Phinney