Retirement Income

Practice Management

- Insight: Traditional ways of discussing risk — relying on terms such as “variance” and “standard deviation” — are neither intuitively nor emotionally meaningful to clients. Behavioral finance bears out this disconnect.

- Implication: Clients who don’t understand risk are more likely to make ill-informed decisions when there is market volatility. Clients potentially suffer subpar returns from their behavior, studies show, and advisors face retention challenges during periods of volatility as a result.

- Implementation: Specific questions and exercises can help clients define the risk that they ascribe to each specific goal.

Studies often reveal a disconnect between the way risk is discussed with clients and the way clients understand it. Terms such as variance, standard deviation, Sharpe ratios and the efficient frontier may clearly quantify volatility for academics and investment advisors but may sound like Greek to most clients. The gap in understanding around risk opens up clients — and advisors — to potentially negative effects.

Clients rarely wake up in the morning fretting if their portfolio’s standard deviation is higher than a benchmark. Instead, they worry about the odds of missing real-life financial goals. Nearly half, 46%, of individuals polled in a 2014 study by the Cass Business School at City, University of London and the Pensions Institute said they examine their savings and investing risk in terms of specific savings goals.1 Only 27% of those polled find investment matters easy to understand.1

Clients who don’t understand risk are also likely to misunderstand what to expect from their portfolios. In a separate 2017 survey of investors, 20% said they don’t know how much they stand to lose from their portfolios in a bad year. That lack of understanding translates into inaccurate expectations. In the same poll, 71% of those asked thought a balanced portfolio wouldn’t fall by more than 20% in a bad year.2 But in reality, the average investor loss from asset allocation funds was 31% in 2008, according to a 2016 DALBAR report. If risk isn’t put into terms clients understand, volatility can surprise them.

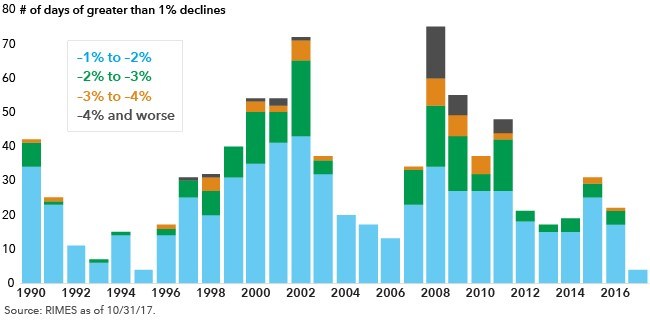

Now’s a good time to challenge yourself to see if clients understand their portfolio’s risk since more surprises could be coming. The market’s volatility has been at record lows and could very possibly increase, prompting investors to consider for the first time in years if they feel they were adequately educated about the risks by their investment advisor.

Eerily low volatility: Are your clients ready if market volatility picks up?

Avoiding counterproductive abstractions

Talking to clients about risk in a somewhat academic manner may feel natural for advisors. Advisors have been trained and tested to think about risk in the context of the modern portfolio theory (MPT). MPT theorizes it’s possible to construct an “efficient frontier” of optimal portfolios offering the maximum possible expected return for a given level of risk. But while many advisors have become adept at explaining these concepts to clients, these efforts are missing the larger point: Concepts such as variance and standard deviation aren’t intuitively or emotionally meaningful to clients. It’s one thing to describe what it’s like to ride a roller coaster, but something altogether different to do a 360-degree inverted loop at 90 miles per hour.

Clients often can’t relate to technical, abstract terms about risk to their personal goals. Not making a connection between risk and financial goals also detracts from the true value advisors can provide: the behavioral coaching that keeps clients from making costly investment-related mistakes.

Self-inflicted mistakes by investors who don’t understand markets can be costly over time. Actual fund returns for the average equity fund investor have been just 4.79% annualized the past 20 years through 2016, well short of the 7.68% returns of the Standard & Poor’s 500, according to the DALBAR report. Part of this shortfall is due to investor behavior, which reduces returns. Households with accounts at a large discount brokerage, which traded stocks most frequently, earned 11.4% annual returns, falling well short of the market’s 17.9% return between 1991 and 1996 in a seminal study on the topic.3 “Overconfidence can explain high trading levels and the resulting poor performance of individual investors,” the authors found.

Advisors, too, face challenges if clients don’t understand investment risks. More than a quarter, 28%, of ultra high net worth investors said the complaints “advisor does not understand my risk tolerance” and “advisor only talks about investments and not my overall financial situation,” which are tied for sixth in most popular reasons for changing financial advisors, just after “not returning phone calls in a timely manner,” “not returning emails in a timely manner,” “not being proactive in contacting me,” “not providing me with good ideas and advice,” and delivering results that are low “compared to the overall stock market,” according to Spectrem Group.4

To learn more about overcoming the disconnect between how advisors position themselves and the services that clients most value, please see the article titled: “Reframing Your Value Amid the ‘Advice Revolution.’”

Making risk relevant to your clients

The way advisors have learned to talk about risk and the method clients want to hear about risk are often disparate. But Capital Group has found there could be a better way to handle the subject that builds client satisfaction and deepens the relationship between clients and advisors.

Based on our experience and review of behavioral finance research, we suggest risk be presented to clients in a highly personal matter, rather than as a numbers-based abstraction. Furthermore, you should seek to understand clients’ risk tolerance not as a single descriptor (i.e., “conservative” or “aggressive”), but rather as a series of varying, yet coexisting, attitudes toward risk across a multitude of goals.

How can you address risk in a way that corresponds to how clients feel it? We suggest a two-step process to do this:

- Recognize when clients reflect on risk, they are not thinking about the variability of return versus the benchmark — rather, they assess risk as the probability of not reaching their goals.

Gain a deep understanding of your clients’ goals. You will have to draw out information, attitudes and feelings from your clients, who may never have delved that deeply into their emotions connected to their goals. You need to help them not only articulate these goals, but also prioritize them and express the risk they’re willing to take — or not take — to achieve them. - Help clients identify how much “shortfall risk” they are willing to accept for each goal. At Capital Group, we have developed a system of prioritizing clients’ goals by categorizing them as “essentials,” “enhancers” and “endowments.” For each of these categories, we assign a confidence level — a function of how much risk of falling short of that goal that clients are willing or able to assume. The more important the goal, the higher the required confidence level, and the less risk clients will be willing to take to achieve the goal.

To learn more about Capital Group’s essentials, enhancers and endowments system of prioritizing goals, and assigning appropriate risk levels to these goals, we invite you to read “Successfully Implementing Goals-Based Planning.” Regardless of whether you use this system, your focus should be on talking to clients about risk in a way that directly relates to their hopes and fears related to their goals.

Tools for helping clients understand risk

By thinking creatively, you can develop practical tools to uncover clients’ true feelings about what risk levels they are willing to assume for different goals. One approach would be to create a questionnaire to help clients articulate how they feel about different types of risk.

Some possible questions might include:

- What would upset you more: Having to cut back your planned annual winter vacation from eight weeks to six weeks … or not being able to leave as much money as you had wanted to those charitable organizations you support?

- What would cause you to lose more sleep: If I told you that you risk outliving your resources … or if I said you might not be able to pay for the full cost of sending your children to a prestigious private university?

- What would make you happier: If I told you that you will be able to retire two years earlier than expected …. or if I said that you are on track toward buying the vacation home in Napa Valley that you have desired?

- What would most cause you to change your investment strategy: If I told you that, given your current circumstances, you have a 30% chance of running out of money by the time you reach 90 … or if I said you would probably be able to give only half as much to charity as you had intended?

As an alternative, or a supplement, to the types of questions mentioned above, you could create a sheet that asks clients to rank their feelings about achieving, or not achieving, specific goals. Such a sheet could look like this:

On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the most disappointed and 5 being the least disappointed, rank the following statements:

___Having to depend on your grown children to provide some of the financial resources you might need to pay for some type of long-term care (e.g., an extended nursing home stay)

___ Having to scale back your annual winter vacation from a tropical location to one inside the United States

____Being able to leave only half as much as you would like to bequeath to your favorite charities

____Being forced to take on a significantly more modest retirement lifestyle due to your assets being less than planned

___Having to abandon plans to extensively remodel your home

The process of going through exercises like this with your clients can help you learn a great deal about their priorities and how they view risk. This information not only helps you build portfolios that maximize the probability of reaching the most important goals, but it also guides your communications with clients in the future. The more you understand how your clients think about risk, the better equipped you are to keep them focused and committed to the investment strategy.

Talking to clients about risk in language that resonates with them is essential to the health of your practice. By centering the conversation around your helping clients achieve their goals, you are building strong relationships and showcasing the greatest value that you provide as an advisor.

1 “How Do Savers Think About and Respond to Risk?” by David Blake and Alistair Haig was based on a survey collected by YouGov Omnibus from 2,000 respondents online in Great Britain. The respondents were compiled from a panel of 400,000 people to create a representative sample based on age, gender, region and social grade. The survey was published in 2014 by the Pensions Institute and the Cass Business School at City, University of London.

2 “10 Years After the Crash: Investors Still Don’t Understand Investment Risk.” Based on a survey of 2,039 adults conducted by YouGov for Scalable Capital. Published in October 2017.

3 “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors” by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean. Studied 66,465 households with accounts at a large discount broker between 1991 and 1996.

4 “Advisors Must Understand the Risk Tolerance of Investors.” Spectrem Group updated as of the third quarter of 2017. Ultra high net worth investors defined as those with a net worth of $5 million to $25 million, not including their primary residence.

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Client Conversations

-

Market Volatility

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Chris Gies

Chris Gies