Marketing & Client Acquisition

Practice Management

- Non-index mutual funds can be more tax efficient than many investors think relative to ETFs.

- Low interest rates can reduce the opportunity cost of paying taxes on capital gain distributions.

- Taxes are important to investors, but tax efficiency is secondary to good investment results.

Mutual funds can bring diversification, cost efficiency and liquidity to investors. But tax efficiency isn’t something mutual funds are usually known for — due to a number of misconceptions.

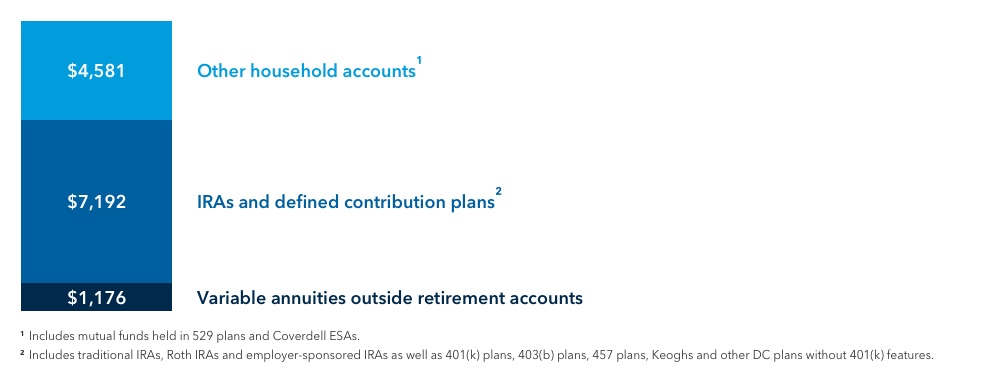

The taxation of mutual funds is largely an academic discussion since more than half, 56%, of households’ mutual fund assets are held in either a tax-advantaged IRA or a defined contribution plan, according to the 2017 Investment Company Institute Fact Book. But for investments held outside such accounts, it’s a different story. A portion of the roughly 35% of households’ mutual fund assets held outside of IRAs or defined contribution plans are in taxable accounts, although some are in 529 plans and 9% are in variable annuities outside of retirement accounts as well. “There can be a reluctance with (investing in) mutual funds” in taxable accounts with some clients,” says Michelle Black, head of wealth advisory at Capital Group.

Not all mutual fund assets are in tax-advantaged accounts

Household mutual fund assets (in billions)

Source: 2017 Investment Company Institute Fact Book

A closer examination, though, shows that many widely held criticisms about the relative tax efficiency of non-index mutual funds have a lesser real-life meaning for investors. A few of the tax myths investors need to be aware of regarding mutual funds include:

Myth #1

The myth: Capital gains distributions by non-index mutual funds are a significant tax drag.

The reality: These distributions typically change the timing of taxes, not the tax bill itself.

When a mutual fund manager sells an investment for a gain and distributes the gain to shareholders, a taxable event might occur. This involves investors who bought a fund after the assets were sold. “Investors don’t like the idea of buying into embedded gains” since many funds hold positions with unrealized capital gains, Black says.

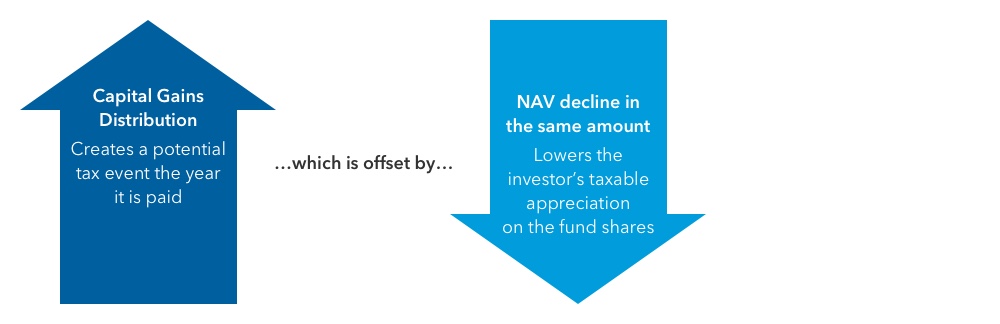

But the real tax impact is smaller than widely thought due to the way mutual funds are priced. It’s more of a timing issue. When a mutual fund pays a capital gains distribution, the fund’s net asset value (NAV) is lowered by the same amount at the same time. This reduces the investor’s unrealized gain on the mutual fund shares and provides a potential tax offset if the fund shares were to be sold.

Consider the following example of what would appear to be an unfortunate tax situation: An investor buys a mutual fund share at a NAV of $10. The very next day, the fund announces a long-term capital gains distribution of $1 a share for shareholders of record. That creates a capital gain taxable event on the $1 distribution.

But in reality, the event is more about timing. When the capital gain is paid out to shareholders, the fund’s NAV declines by the amount of the distribution. In this case, the NAV on the fund falls by $1 to $9. This means the investor would have an unrealized loss on the fund itself of $1. If the investor sold the mutual fund shares that day, the tax loss on the fund shares themselves would offset the capital gains distribution, resulting in no tax due. To be clear, if the investor held onto the shares instead and sold down the line, they would need to pay taxes on any realized capital gains they did enjoy.

Capital gains distributions: The whole tax picture

NAV is reduced after a capital gains distribution, offering a potential tax offset

Source: Capital Group

The takeaway: Assuming investors would eventually sell the fund shares, they aren’t paying more in taxes, they’re just accelerating the payment, Black says. Investors lose control of the tax event — that is an inefficiency, but when interest rates are low, it’s not a major financial consideration. Investors often use cash or fixed income securities to pay the tax on capital gains distributions, Black says. Missing out on roughly 1% annual returns on cash to pay taxes isn’t a major concern. “Your opportunity cost is not that high,” Black says.

Myth #2

The myth: Exchange-traded funds are always more tax efficient than mutual funds.

The reality: Mutual funds and ETFs are on equal footing with many common taxable events.

Some investors buy high-yield or fixed income ETFs tied to indexes — as opposed to mutual funds or ETFs where managers select securities — thinking they’re more tax efficient when dealing with income. But ETFs have the same tax drag to shareholders as open-end mutual funds when it comes to dividends, interest and sales of fund shares by shareholders, says Casey Dregits, a senior advisory specialist at Capital Group.

Interest income and dividends are typically taxed the same whether they’re paid through a fixed income ETF or a mutual fund: They’re still considered ordinary income. Dividends and taxable bond income is “not tax efficient in any vehicle” in a nonretirement account, Dregits says. ETFs do have a potential tax advantage with capital gains distributions due to their structure, but that does not extend to dividends and interest payments.

Myth #3

The myth: All mutual fund capital gains distributions are taxed the same.

The reality: Long-term investment strategies can reduce less tax efficient short-term capital gains.

Reducing realized short-term capital gains is a good idea for most tax-aware investors, as these distributions are taxed at usually higher ordinary tax rates. Some mutual funds can minimize these distributions with long-term investment strategies, relative to peers that trade more frequently.

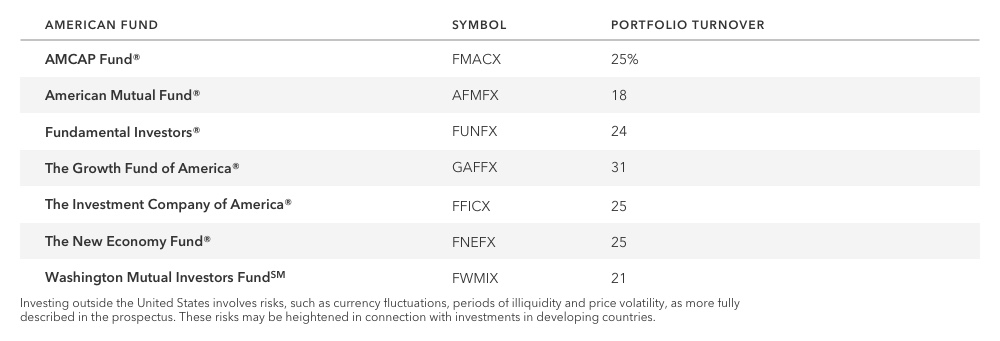

There’s an easy way to gauge whether a fund is less likely to generate short-term gains: Turnover. A fund’s turnover tells you roughly what percentage of a portfolio has changed over the past year — 30% turnover or lower generally indicates a buy-and-hold system. Lower turnover leads to a deferral of the cost of realizing capital gains. “Turnover and tax efficiency have a negative correlation,” Black says. “The lower the turnover, the higher the tax efficiency.” Tax efficiency refers to the ratio of pretax to posttax results.

Mutual funds directly tied to major indexes, like the Standard & Poor’s 500, tend to have low turnover since the securities they own aren’t changed frequently. But funds managed by portfolio managers who choose securities can have varying degrees of turnover. All seven of American Funds’ U.S.-focused equity funds — due in part to the long-term strategy deployed by many Capital Group portfolio managers — were all in either the first or second lowest quartile of turnover of their respective categories. These were among open-ended mutual funds at the end of 2015 on Morningstar’s data, which is the latest comparable data available at the time the analysis was done in 2017.* All seven of these funds had turnover of 31% or lower as of the most recent fiscal year-end of the fund as of June 30, 2017.

Capital Gains Distributions: The Whole Tax Picture

NAV is reduced after a capital gains distribution, offering a potential tax offset

Source: Funds shown are U.S.-focused equity American Funds. Portfolio turnover based on most recent fiscal year-end of each fund as of 6/30/17. Symbols are for Class F-3 shares.

Myth #4

The myth: Funds with managers who select investments never have a tax edge over index funds.

The reality: The tax efficiency of mutual funds with managers who select investments can improve in down markets.

Mutual funds not based strictly on an index can offer additional tax advantages during periods of declining asset values, according to a 2015 research paper “Mutual Fund Governance and Tax Efficiency” that appeared in The Journal of Wealth Management, co-authored by D.K. Malhotra, professor of finance at Philadelphia University. Just as mutual funds may distribute taxable capital gains during up years for the market, they can offset gains with capital losses during down years for the market. This is another potential offset to capital gains. “Turnover’s effect on tax efficiency depends on conditions in the securities markets: A falling market leads to greater tax efficiency as a result of security sales at depressed prices,” Malhotra wrote.

Nonetheless, investment professionals caution that while taxes are a consideration in investing, they shouldn’t be the driving factor. Investors should focus on after-tax results, not taxes, Black says. It’s what investors keep that matters. If a non-index mutual fund has better results, the amount investors keep may still be greater than with an index on an after-tax basis.

So while taxes matter, returns matter more, Black concludes. “Don’t let taxes wag the investment dog,” Black says.

*Turnover of The Growth Fund of America®, AMCAP Fund®, Fundamental Investors® and The New Economy Fund® were compared with the 386 active funds in the Morningstar Open-End U.S. Large Growth Fund category as of 2015. The Investment Company of America® and Washington Mutual Investors FundSMwere compared with the 330 active funds in the Morningstar Open-End U.S. Large Blend category as of 2015. American Mutual Fund® turnover was compared with 328 active funds in the Morningstar Open-End Large Value category as of 2015.

Use of this website is intended for U.S. residents only.

Michelle Black

Michelle Black