Monetary Policy

Fed

The Federal Reserve announced on December 15 that it will move more quickly to end its economic stimulus, doubling the rate at which it winds down (or tapers) its asset purchase program. This puts the Fed on track to stop buying bonds by March, and clears a path for it to raise interest rates shortly thereafter. Fed officials’ latest median projections indicate they may raise rates three times next year, and three more times in 2023.

Here are some top takeaways on the news and thoughts on the year ahead from Capital Group economist Darrell Spence and fixed income portfolio managers Ritchie Tuazon and Tim Ng.

1. Getting ready for rate hikes in 2022

Ritchie Tuazon and Tim Ng

The most important signal from speeding up the taper is that it opens the door to more 2022 rate hikes. But, while Fed policy changes are an inflection point that can rattle markets, it is important to keep this news in perspective.

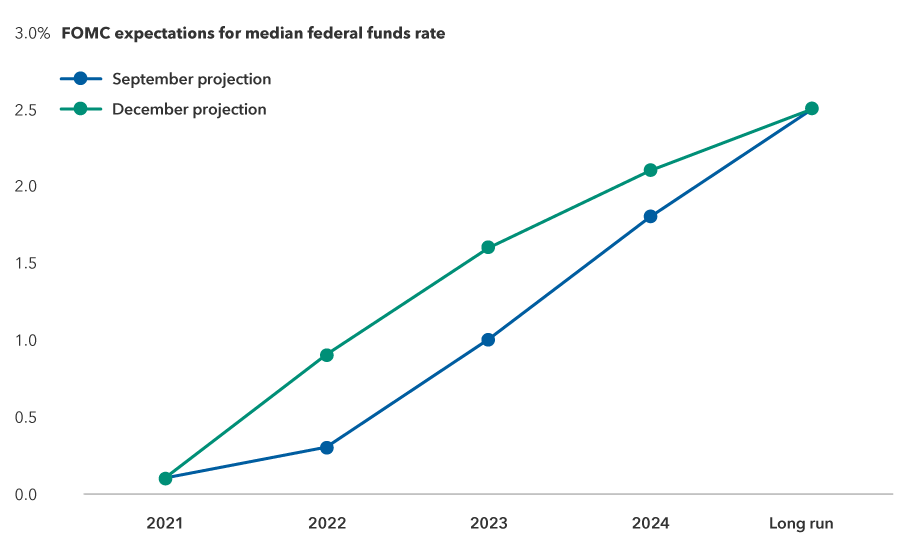

The Fed’s latest “dot plot” chart shows that most of its governors now anticipate three rate increases for 2022. This is big pivot from September, when only half of the members of the Federal Open Market Committee predicted rates would rise at all in 2022. It is also above market consensus of two hikes in 2022. Fed Chair Jerome Powell also indicated that the committee will start discussions on reducing the size of its balance sheet.

Now our base case is that the Fed will raise rates three times next year. Despite the hawkish tone of the announcement, stocks and TIPS did well after the announcement, and the yield curve steepened. If risk assets hold up and financial conditions remain loose, the Fed will have the green light to move even more aggressively to address inflation.

Near term rate hike expectations have risen due to high inflation

Source: Federal Reserve. As of December 15, 2021.

The December 15 announcement also represents a hawkish shift from Powell, who was renominated by President Joe Biden in November for a second term. Powell had previously defended the view that the inflation we see today was “transitory” and would resolve itself, but he abandoned the term altogether in his statement this week.

In a press conference, Powell stated that November’s jobs report, which included upward revisions to prior jobs reports, coupled with November’s consumer price index (CPI) update, which showed a substantial increase to inflation, convinced him it was time to speed up the taper.

Powell noted that U.S. labor force participation numbers are still “disappointing” but said that he believes the economy is still making rapid progress toward maximum employment. “We have to make policy now,” he said. “And inflation is well above target. So, this is something we need to take into account.”

The Fed appears to be interpreting the Omicron COVID-19 variant as an inflationary impulse but does not appear to be too concerned about its risks. Powell said that people are learning to live with the virus despite recurring waves, suggesting the economic implications may be limited.

In addition to renominating Powell, Biden has also named new Fed Board appointees in recent weeks who are likely to tilt dovish, but we do not expect that they will rock the status quo and impede the new accelerated tapering schedule. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly, who has been among the most dovish members of the Federal Open Market Committee, was among the first to come out and say the taper should be sped up.

Others who are considered doves — such as Lael Brainard, who has been nominated to be the Fed’s new vice chair, and John Williams, president of the New York Fed — have also been making speeches indicating that, if inflation is above mandate, they will do what is necessary to keep it under control. This concern over inflation is bipartisan, so there is likely to be little political resistance to moving rates up to fight inflation.

At the end of the day, however, we are still going to have low rates and low yields for the foreseeable future. The Fed’s longer run dot plot projections did not move, and calculations from the Atlanta Fed show the market expects the federal funds rate to be around 1.5% at the end of 2024, which is still a highly accommodative environment.

2. U.S. growth likely to slow down but stay solid

Darrell Spence

We see tempered growth for the United States in 2022 as fiscal stimulus wanes and the Fed begins to remove accommodation. Our base case is 2.5% to 3% GDP growth, which is still a respectable rate. And although any period of monetary tightening can generate higher market volatility, we on the Capital Strategy Research (CSR) team expect risk assets to remain supported by strong earnings. Valuations are high relative to history, but they are not exorbitant considering the current, and projected, level of interest rates. A mild correction is not out of the realm of possibility, but we do not expect a systemic market decline.

That said, there are likely to be more headwinds — in particular, inflation — hitting the economy in 2022 than there were in 2021. While this is not a complete surprise, given where we are in the post-COVID rebound, we will be watching closely for signs that they are exerting more of a drag on economic activity than currently expected as we move toward the end of the year.

3. Supply chain issues are set to persist

Darrell Spence

Currently, stimulus-induced demand is meeting COVID-restricted supply, and this is creating imbalances that are keeping inflation elevated.

With no more stimulus checks, federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) grants, emergency unemployment benefits, or debt and eviction moratoriums, it seems likely that demand will soften. Where supply goes is more uncertain. If COVID-induced bottlenecks clear up and supply increases, a new equilibrium could occur with inflation around pre-pandemic levels. This is the “transitory” scenario the Fed had been assuming.

While much is still unknown about Omicron, its arrival does suggest that COVID will be with us for a while longer. As such, the “transitory” period — i.e., the period where COVID is impacting supply and generating inflationary pressures — has likely been extended another six to 12 months, and there is a risk that inflation begins to have a more negative impact on economic activity during that period.

Unfortunately, there is very little the Fed can do to increase supply. Rather, to reduce inflation, it would need to suppress demand, which essentially means putting the economy into a slowdown or recession. However, we still do not know how willing it will be to push down an economy, particularly one that may not be at their definition of full employment, just to break the back of inflation.

All that said, if one has a multiyear timeframe, “transitory” still looks like a strong possibility. Many of the factors that caused inflation to remain low in recent decades — in particular, globalization and advances in technology — are still in play. These factors should help moderate inflation in the long term, but in the near term, COVID and its related issues are likely to dominate the inflation outlook.

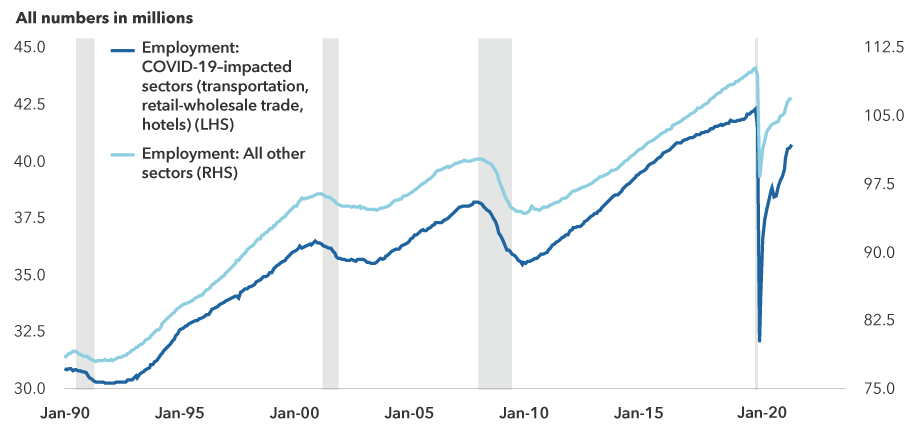

Employment is laboring toward full recovery

Sources: Capital Group, Haver. Data as of September 2021. Shaded areas represent recession periods as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

4. Equity markets are likely to stay resilient

Darrell Spence

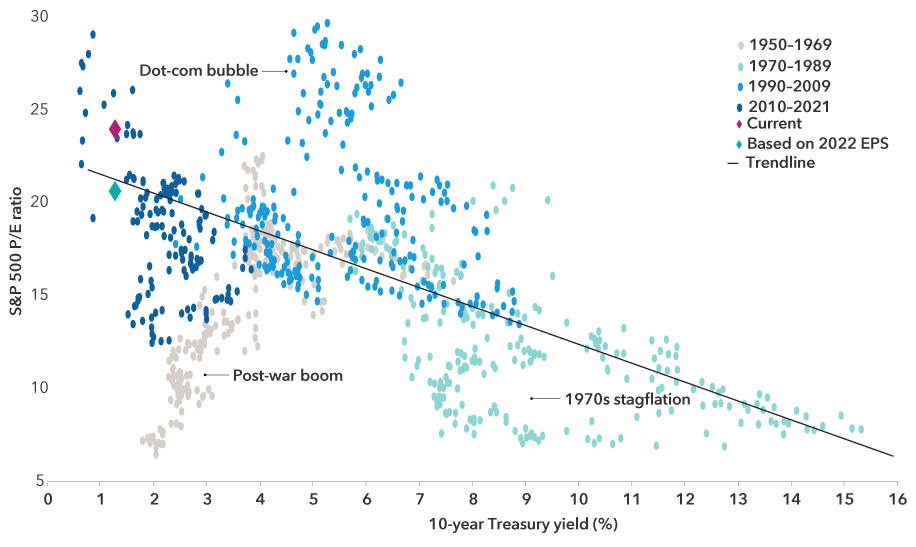

We currently expect that equity markets will be able to ride this out next year, as slow but positive economic growth should support an increase in corporate profits. Understandably, there is a lot of concern about valuations, as the market price-to-earnings ratio does look high relative to history. However, it has been that way for years, yet the market has continued to march higher. Had one stayed out of the market due to concerns about valuations, they would have missed a lot of opportunity.

One cannot look at valuations in a vacuum. They need to be looked at in the context of the interest rate environment. The fact is that low rates can support higher valuations (assuming the economy is not in distress, and we do not think it is). Looking ahead to 2022, it is possible that tighter monetary policy, and higher rates, could put some downward pressure on valuations, but we also expect that an ongoing recovery in earnings could offset much, if not all, of that contraction.

What level of interest rates might be problematic?

Sources: Capital Group, FactSet, Federal Reserve, Standard & Poor's. Dots represent monthly data from January 31, 1950, to August 31, 2021.

As an aside, there is a school of thought that suggests rising yields will not start to exert significant downward pressure on the equity market until the 10-year Treasury yield reaches 5.0%, because that is the level at which the correlation between bond yields and equity prices has reversed, twice, over time. This flip-flop in correlation could be total coincidence, but it could also have occurred because yields above 5.0% indicate that inflation has become a dominant factor driving valuations. If there is anything to the 5.0% threshold, then the current 10-year yield, at 1.4%, appears to be a long way away from a level that has, at least historically, created a headwind for the equity market.

While we will likely not see the gains that we have seen over the past year or so, we on the CSR team believe single-digit equity returns to be attainable as the market rises in line with, or slightly less than, earnings growth in 2022.

Standard & Poor's 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks.

Stay informed with our latest insights.

Our latest insights

RELATED INSIGHTS

-

-

Interest Rates

-

Municipal Bonds

Don’t miss out

Get the Capital Ideas newsletter in your inbox every other week

Ritchie Tuazon

Ritchie Tuazon

Tim Ng

Tim Ng

Darrell Spence

Darrell Spence