Politics

This week marks the beginning of the endgame in Washington, D.C., as Democratic Party leaders seek approval for a multitrillion-dollar legislative agenda while — at the same time — attempting to avoid an ugly battle over the U.S. debt ceiling and a potential government shutdown.

On the legislative front, the range of potential outcomes remains broad. The big-ticket items at stake include a roughly $1 trillion infrastructure bill and a $3.5 trillion spending plan focused on health care, education, family support and climate change initiatives.

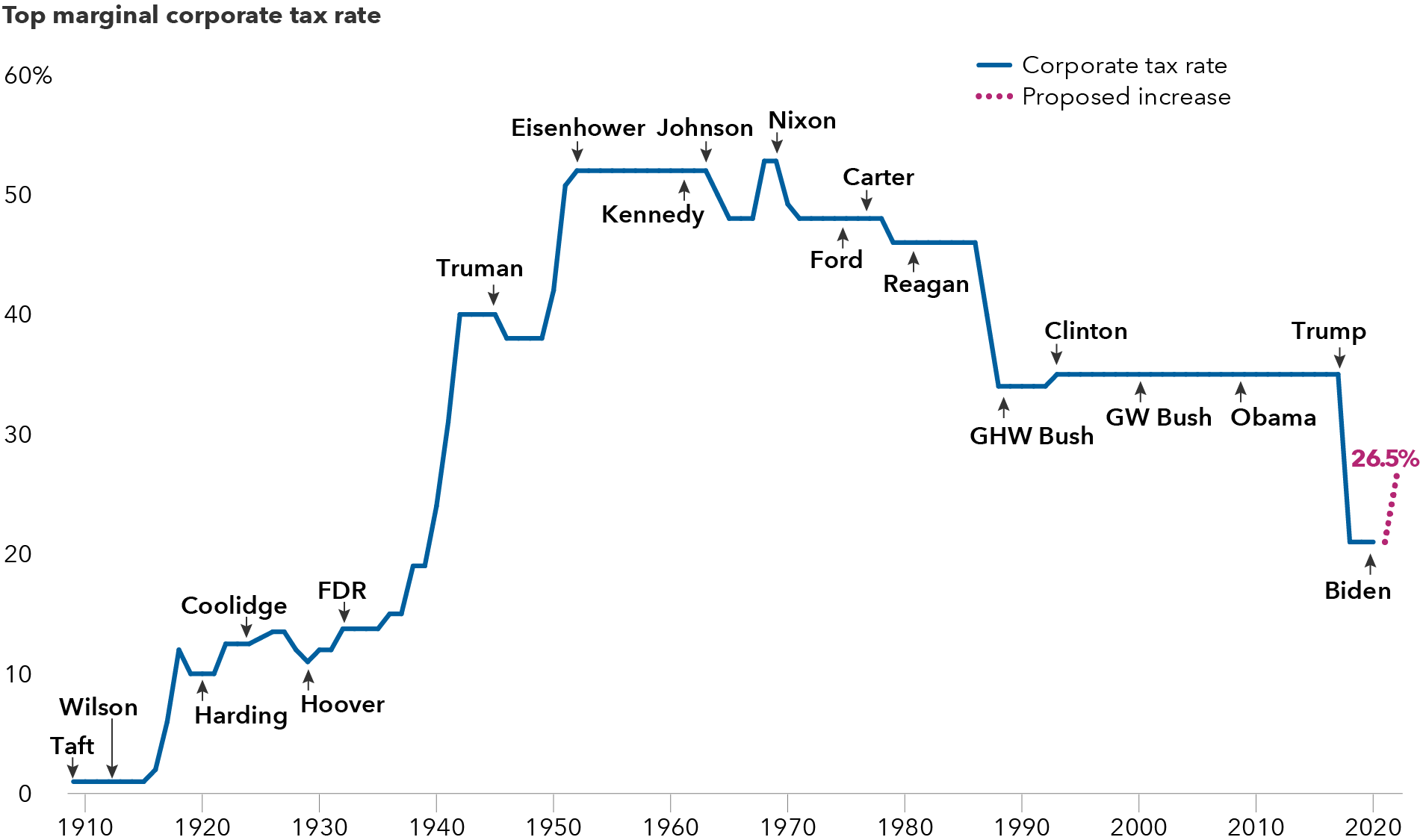

To help pay for these ambitious programs, a series of tax hikes are on the table, including an increase in the top marginal corporate tax rate, which would go from 21% to as high as 26.5%, according to a recent proposal in the House of Representatives. Higher corporate taxes will gain approval, in my view, although I think 25% is more likely to be the final number.

U.S. corporate taxes are likely heading higher

Sources: Capital Group, Strategas. As of 9/23/21.

Investors who may be worried about drastically higher taxes or runaway spending should keep one key factor in mind: The outcome will be shaped by centrist Democrats in the Senate. That means a big chunk of what’s creating headlines today will be seriously scaled back, in my opinion, as progressive goals meet the reality of the Democratic Party’s slender majorities in the House and Senate.

Here’s a brief look at three of the major issues taking center stage this week — and probably for the next several weeks — along with an assessment of the likely outcomes. In these highly partisan times, please note, what follows is not a matter of “taking sides,” but rather of scanning the policy landscape to assess the implications for investors. As I always say to the investment team at Capital Group, this is analysis, not advocacy:

1. $3.5 trillion spending package will be cut roughly in half

While one could argue that $3.5 trillion in spending over 10 years isn’t all that much compared to the size of the U.S. economy, there simply isn’t enough support in Congress for such a large figure. After all is said and done, the top-line number in the budget reconciliation bill will probably slim down to $1.5 trillion or $2 trillion.

Revenue generated by proposed tax increases probably will amount to about $500 billion to $750 billion over the next decade, with most of the new tax burden falling on corporations. The rest will be deficit funded or wished away via fuzzy economic growth assumptions. Individual income tax hikes will account for a much smaller portion of the revenue pie and focus mostly on high earners. Those making more than $400,000 a year will probably see the top income tax rate rise to 39.6%, and the capital gains tax could climb to 25% or so. A 2% excise tax on stock buybacks is also in the mix and might be seen as a politically feasible way to raise needed revenue.

“The dilemma that Democrats face is how to fit $3.5 trillion worth of big ambitions into a smaller package.”

Over the next few weeks, the dilemma that Democrats face is how to fit $3.5 trillion worth of big ambitions into a smaller package. Major spending priorities will collide and there remains a chance, given complicated disputes within the Democratic Party, that the entire legislative agenda collapses. Coming up empty-handed would be a political disaster for Democrats as they head toward the 2022 midterm elections, but this scenario can’t be ruled out.

A pivotal first test of the endgame will come on Thursday, September 30, when the House is expected to vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill. Some leaders in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party have argued that this bill should only pass in tandem with the broader reconciliation package. Otherwise, they feel they will lose leverage over the size and contours of the larger package. Other Democrats think it’s more important to bank a big “win” on infrastructure to create momentum for the rest of the legislative agenda.

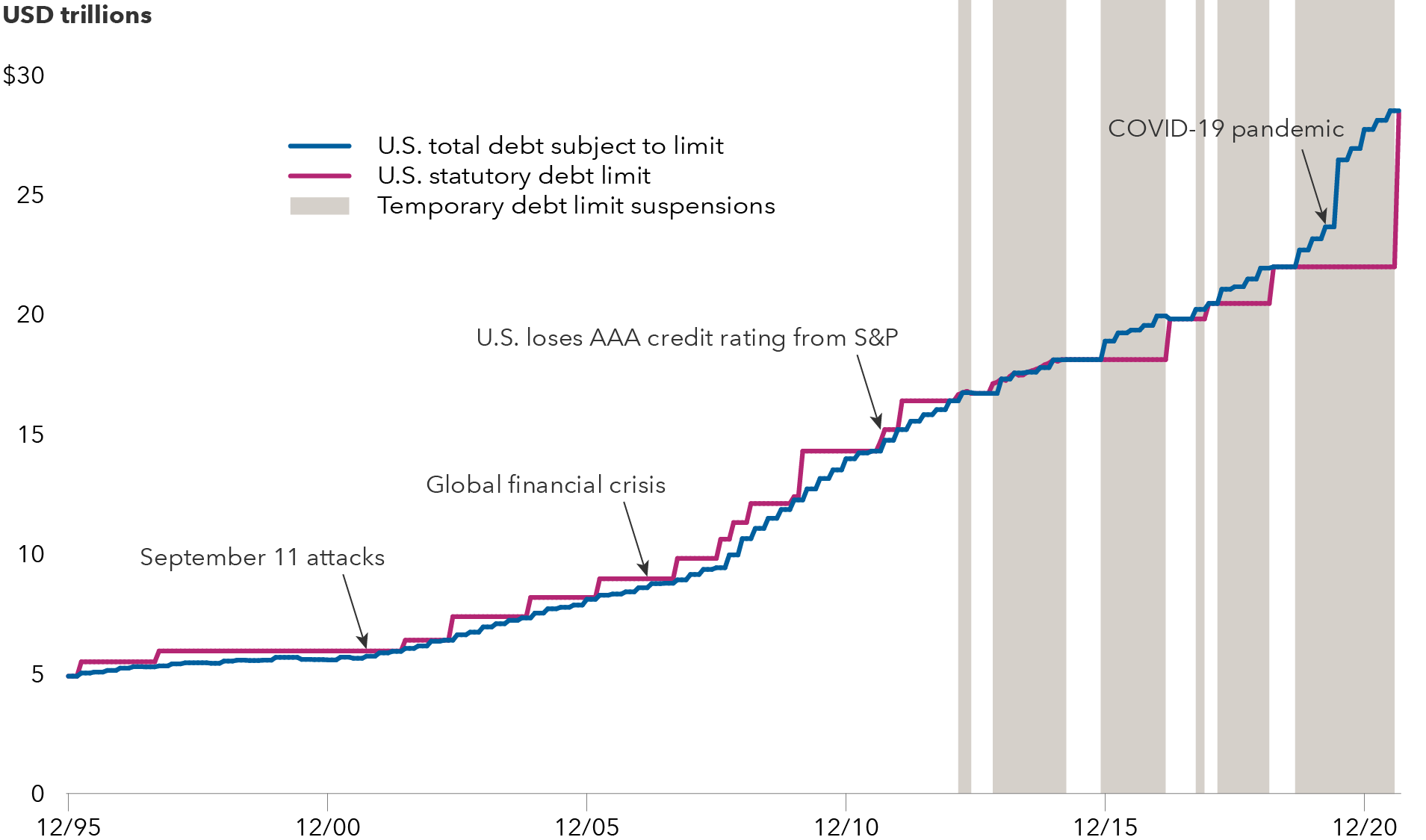

2. Democrats will have to raise the debt ceiling on their own

Remember the debt ceiling standoffs of 2011 and 2013? They’re coming back with a vengeance. If the federal debt limit is not raised or suspended soon, the government could lose its legal authority to borrow money and perhaps fall for the first time ever into technical default. So far, Republican Party leaders are refusing to vote for an increase or suspension, and I don’t think they are bluffing. They relish the idea of forcing Democrats to authorize on their own a new debt level of $30 trillion or more. The GOP midterm attack ads write themselves.

Raise the roof: A debt ceiling standoff could get ugly

Sources: Capital Group, Refinitiv Datastream, U.S. Department of the Treasury, U.S. Office of Management and Budget. As of 8/31/21. Periods in which the statutory limit has been suspended are reflected by the shaded vertical bars, namely from February 2013–May 2013; October 2013–March 2015; November 2015–March 2017; September 2017–December 2017; January 2018–February 2019; and August 2019–July 2021.

The GOP view is that Democrats have the power, and thus the responsibility, to lift the debt ceiling with a simple majority vote in the Senate as part of the budget reconciliation process. My concern is that the political brinkmanship in the weeks ahead — against the backdrop of so many other high-stakes issues coming to a head — could lead to an “accident” in which the government falls into technical default, an event that would roil the markets and raise questions about U.S. political and financial stability.

Keep an eye on potential creative maneuvers Democrats may use at the eleventh hour, including invoking the Treasury’s obscure legal authority to mint trillion-dollar platinum coins and deposit them at the Federal Reserve to top up its checking account. (While this sounds odd, it is in fact considered a feasible option by some).

“The threat of a serious debt limit crisis isn’t trivial.”

This is a nonconsensus view, but I think the threat of a serious debt limit crisis isn’t trivial. I would put the odds at 10% to 15% if the issue isn’t resolved soon. One could argue that we shouldn’t have a debt limit in the first place. Only Denmark and Poland have such rules, and they don’t create U.S.-style crises. But the debt limit remains part of the U.S. political landscape and it isn’t going away anytime soon.

Meanwhile, the government’s funding is set to expire on Friday, October 1. If Congress takes no action, we could see another partial government shutdown. But I think Republicans will agree to extend the funding through early December, saving their ammo for a potentially dramatic debt ceiling showdown.

3. Midterm elections will produce a divided Congress

All these momentous events are happening against a backdrop of what could be one of the more consequential midterm elections in U.S. history. Make no mistake, every move in Washington right now is being carefully calculated with the midterms in mind. While the election is still more than a year away — and that’s a lifetime in politics — history suggests we will see a backlash against the party in power that will result in Republicans taking back control of the House and potentially the Senate.

Democrats are certainly worried about this outcome, which is why they feel the urgent need to pass their ambitious agenda now. Assuming history repeats itself, Republican control of the House or the Senate will end the affirmative phase of Joe Biden’s presidency and the Democratic Party’s lofty legislative ambitions.

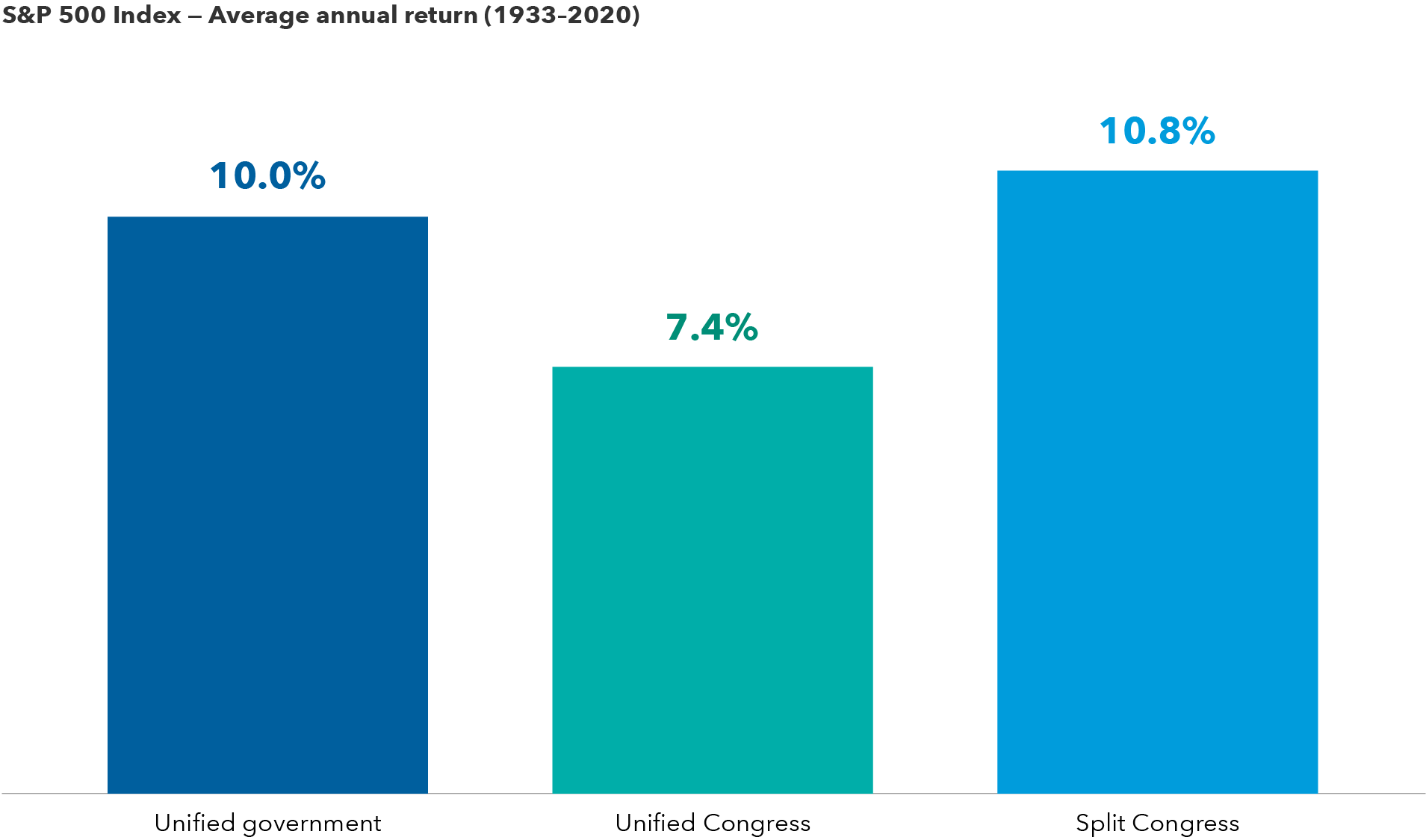

Returns have been strongest under a split Congress

Sources: Capital Group, Strategas. As of 12/31/20. Unified government indicates White House, House and Senate are controlled by the same political party. Unified Congress indicates House and Senate are controlled by the same party, but the White House is controlled by a different party. Split Congress indicates House and Senate are controlled by different parties, regardless of White House control.

Whether you think that’s a good outcome or bad outcome, historically speaking, it appears to be the market’s favorite choice. From 1933 to 2020, under unified governments or a unified Congress, the average annual return for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index has fallen into a broad range from roughly 7% to 10%. When Congress is split, however, the average was 10.8%.

In my book, that’s a nice nonpartisan return.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks. The index is unmanaged and, therefore, has no expenses. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite Index is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.

Matt Miller

Matt Miller