Midterm elections occur at the midpoint of a presidential term in November, and usually result in the president’s party losing ground in Congress. Over the past 23 midterm elections, the president’s party has lost an average 27 seats in the House of Representatives and three in the Senate. Only twice has the president’s party gained seats in both chambers.

This tends to happen for two reasons. First, supporters of the party not in power — in this case, the Democratic Party — usually are more motivated to boost voter turnout. Second, the president’s approval rating typically dips during the first two years in office, as it has with Trump, which can influence swing voters and frustrated constituents.

Republicans currently control both the Senate and House by slim margins. Losing either chamber would effectively end any chance to pass ambitious Republican-sponsored legislation over the next two years, and it would put Trump on the defensive for the remainder of his term in office, Miller explains.

Since losing seats is so common, it is usually priced into the markets early in the year. But the extent of a political power shift and resulting policy impacts remain unclear until later in the year, which can explain other interesting trends.

History suggests lower returns and higher volatility

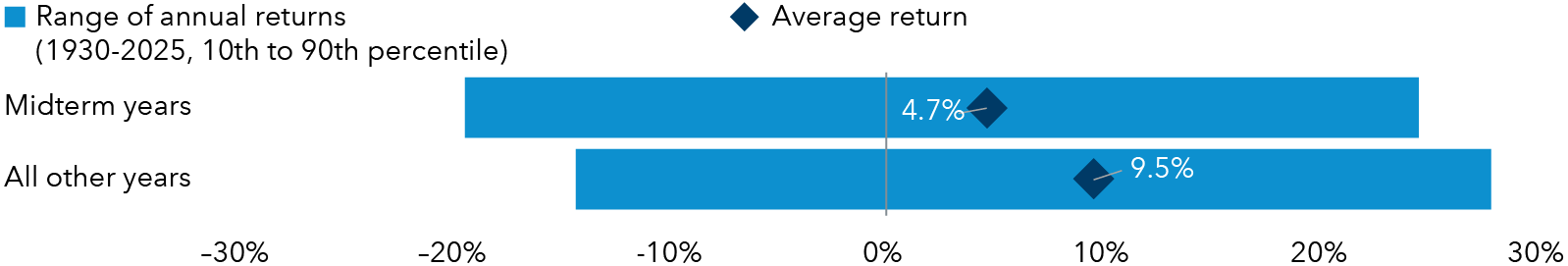

Capital Group examined more than 90 years of data and found that markets tend to behave differently during midterm election years. Our analysis of returns for the S&P 500 Index since 1930 revealed that the path of stocks during midterm election years differs noticeably compared to other years.

Since markets have typically gone up over long periods of time, the average stock movement during an average year should steadily increase. But we found that in the initial months of midterm election years, stocks have tended to generate lower average returns and often gained little ground until shortly before the election.