Liability-Driven Investing

- Pension investors should avoid overreliance on tracking error when assessing long credit managers

- Tracking error provides little insight into a manager’s risk profile and how it aligns with the pension plan’s broader risk management objectives

- Investors should also consider a manager’s potential to deliver downside protection in periods of funded status stress

Pension investors often rely on tracking error as a primary risk metric for evaluating long credit managers. In the view of our liability-driven investing (LDI) team, tracking error in isolation is inadequate for assessing manager risk. While tracking error should be included in these evaluations, we believe investors structuring a LDI portfolio should take a more holistic view that considers their broader pension risk management objectives. Three key areas to focus on are managers’ risk exposures, the correlation of their returns with those of other managers overseeing plan assets and their excess returns in market environments that are typically associated with funded status stress.

What’s wrong with tracking error? Nothing in and of itself. Because it measures the standard deviation of the difference in returns between a portfolio and its benchmark, tracking error is assumed to be a normally distributed measure. However, we argue that not all tracking error is created equal. When considering managers’ tracking error, investors should ask several questions to determine the appropriate fit for the LDI program, and importantly, their broader pension risk management program. These questions can include:

- What are the sources of a manager’s tracking error? Are they taking systematic credit risk or interest rate/curve risk, or are they driving excess returns from security selection?

- Are the sources of these excess returns consistent, or are a few big decisions driving relative results? Is there an ability to clearly articulate the return drivers?

- What are the diversification benefits of adding a particular manager to an LDI program?

- Importantly, how have managers’ relative results stood up in periods of funded status stress, or, said another way, does the manager provide excess returns when plan sponsors need it most?

Consider the kinds of risks managers are taking

Variations in tracking error among different managers often reflect their differing approaches to investment implementation. This points to the importance of understanding the type of risk that managers are taking on. For example, a manager that systematically assumes excess credit risk compared to the benchmark — say, by taking off-benchmark positions in high-yield corporate bonds — may have a large tracking error. Another could take the same amount of credit risk as the benchmark but also produce a high tracking error due to the underlying mix of individual investment-grade securities (BBB/Baa and above) it holds. A third manager could generate a low tracking error by largely avoiding taking positions with the potential for more positive excess returns.

The point is that tracking error alone can be a blunt metric in risk assessments of long credit managers. Pension investors need to understand the types of risk a manager is taking rather than relying on tracking error for evidence of excessive risk-taking. Importantly, pension investors should choose managers whose risk exposures complement the diversification benefits of their current managers. Diversification among managers’ approaches and styles can drive significantly better outcomes than any one manager’s risk and return profile.

Excess return correlation and other factors that determine LDI program diversification

In looking beyond tracking error, a key consideration is the profile of different managers’ excess returns. Ideally, excess return correlations among different managers should be relatively low because the managers deploy different investment styles or hold different securities in pursuit of benchmark-beating returns. For example, one manager might be more focused on security selection and valuation, while another could center its strategy around evolving allocations at the sector and industry level. These different approaches are likely to yield portfolios with vastly different characteristics.

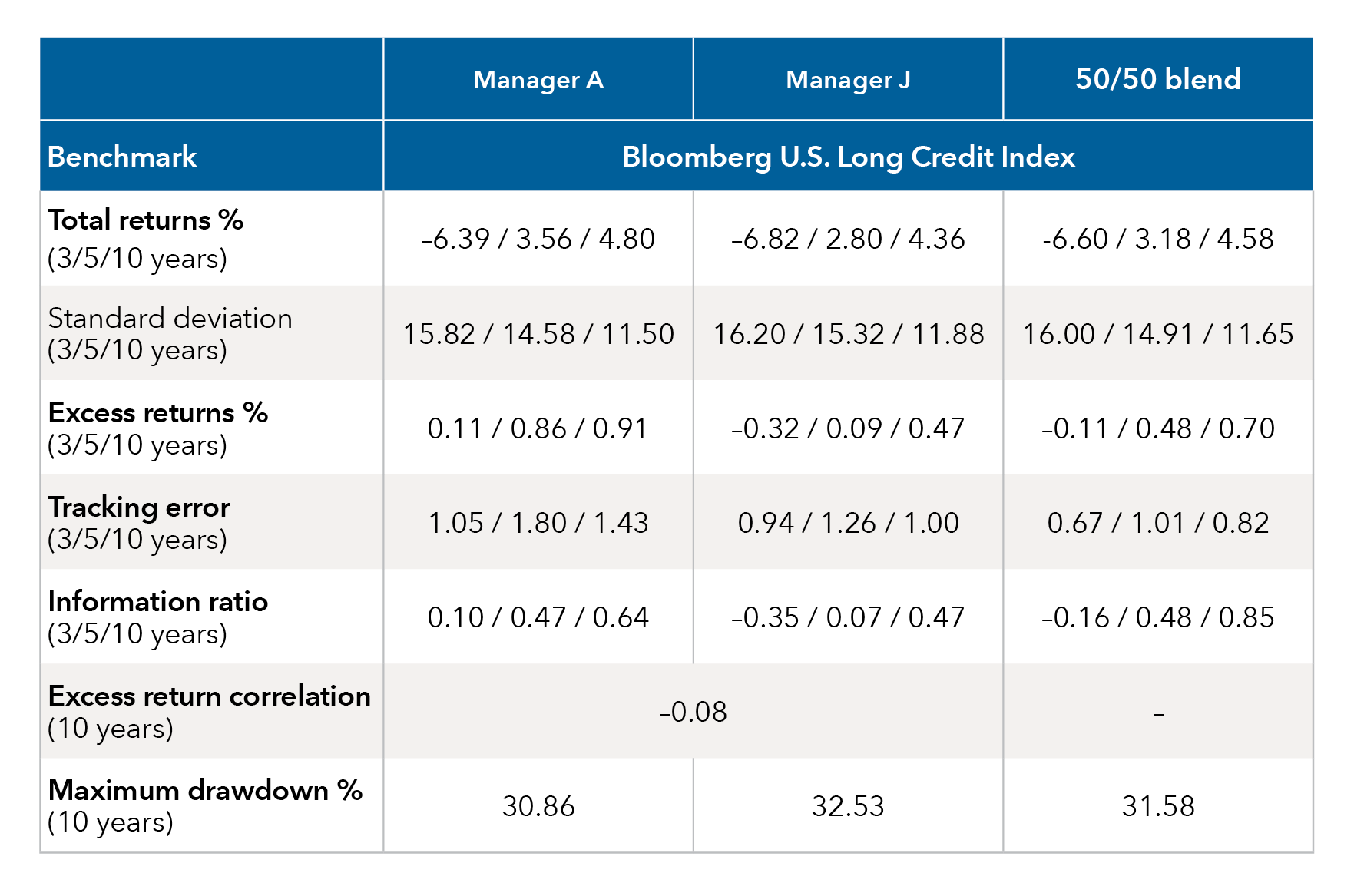

The illustrative case study below shows how blending two managers with different approaches could generate more favorable risk-adjusted results. Take a pension plan that is considering adding manager A to its existing relationship with manager J. In this instance, blending these two strategies equally would have improved upon manager J’s excess returns, tracking error and information ratio. Notably, tracking error is reduced even though manager A has a significantly higher tracking error than manager J. Plan sponsors should also assess how these metrics behaved under stressed market conditions to see if adding a new manager is likely to deliver critical downside protection.

The hypothetical impact of blending two managers

Sources: Capital Group, eVestment. Data as of December 31, 2023. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods. For illustrative purposes only. Annualized standard deviation (based on monthly returns) is a common measure of absolute volatility that tells how returns over time have varied from the mean. A lower number signifies lower volatility. Information ratio measures the portfolio returns beyond the returns of a benchmark (or index), compared to the volatility of those returns. Maximum drawdown is a measure of downside risk over a given time period; it is the maximum loss from the highest point to lowest point of (fund/portfolio) returns before a new high point is reached.

Evaluating results in periods where funded status is often stressed

To put tracking error in perspective, we have developed a holistic quantitative framework for evaluating manager risk based on managers’ excess returns in periods of funded status and financial market stress. The framework looks at four market conditions:

- Negative equity markets – Equity market weakness magnifies the risk of funded status drawdowns for sponsors continuing to hold return-generating assets.

- Spread widening – Broad economic distress can widen spreads and potentially compromise funded status for plans with significant allocations to credit risk.

- Falling rates – Given that most plans are underhedged to interest rate risk relative to their liabilities, falling nominal interest rates typically have a negative impact on funded status.

- Funded status drawdowns – Looking at manager excess results during periods of funded status stress can provide a more holistic picture of downside risk.

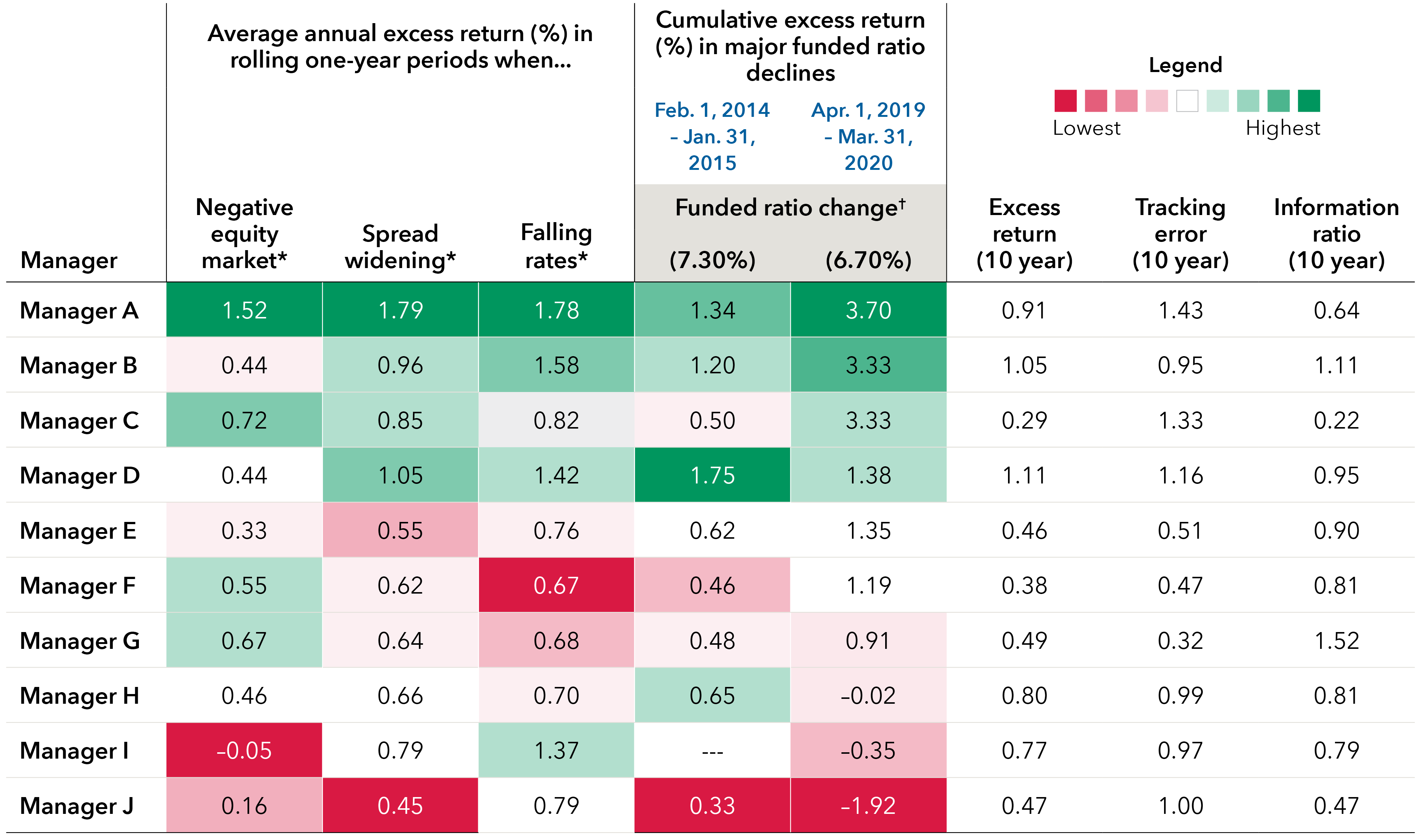

Using this framework, we can evaluate managers’ long-term returns in the context of their results during periods of market stress. In the table below, we compare actual returns of 10 of the largest long credit managers.

Managers’ results in periods of financial market stress

Sources: Capital Group based on data from eVestment. As of December 31, 2023. Data reflects 10 years of rolling one-year returns observed monthly (120 total observations) from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2023. Results are shown since inception for products with inception dates after January 1, 2013. Managers shown are the largest long credit strategies benchmarked to the Bloomberg U.S. Long Credit Index as measured by assets under management. Tracking error and excess return were calculated relative to the same index. Managers’ results are gross of fees. Managers submit data to eVestment on a voluntary basis. As a result, it is possible that some managers are not included in the top 10 list due to incomplete data submissions. Past results are not predictive of results in future periods.

*Negative equity market: Annual change of S&P 500 Index is negative (24 observations). Spread widening: Annual change of Bloomberg U.S. Long Credit Index option-adjusted spread (OAS) is positive (58 observations). Falling rates: Annual change of 30-year Treasury yield is negative (51 observations).

†Two of the largest annual funded ratio drawdowns based on Aon Pension Risk Tracker. Figures reflect the difference between funded ratios at the beginning and end of the drawdown periods.

For a good illustration of the limits of tracking error, we return to managers A and J. Suppose a plan sponsor was trying to choose between the two and the preference was to focus on a “lower-risk” manager. Manager A has a significantly higher tracking error of 1.43, compared with 1.00 for manager J. Therefore, one might assume that manager J is the better choice based on the sponsor’s objectives. However, during major drawdowns in pensions’ funded status, as well as periods of market stress, manager J had some of the lowest returns, while manager A had among the highest. Based on holistic plan outcomes, we argue that manager A provides a better overall risk profile than manager J.

The bottom line

Tracking error is a useful metric for assessing long credit managers, but it is only a starting point. Investors need to dig deeper to get a clear sense of the drivers of tracking error. That means understanding a manager’s risk profile and how it aligns with the pension plan’s broader risk management objectives. Further, it is crucial to focus on a manager’s potential to deliver downside protection in negative funded-status environments. From a total plan perspective, putting line-item statistics like tracking error in the broader context of these risk considerations is likely to produce a better outcome for portfolio construction in an LDI program.

Glossary

Annualized standard deviation (based on monthly returns) is a common measure of absolute volatility that tells how returns over time have varied from the mean. A lower number signifies lower volatility.

Correlation is a statistical measure of how a security and an index move in relation to each other. A correlation ranges from –1 to 1. A positive correlation close to 1 implies that as one moves, either up or down, the other will move in “lockstep,” in the same direction. A negative correlation close to –1 indicates the two have moved in opposite directions.

A credit spread is the difference in yield (the expected return on an investment over a particular period of time) between a government bond and another debt security of the same maturity but different credit quality. Credit spreads measure the perceived riskiness of a corporate bond relative to a safer investment, typically the equivalent government bond; the wider the spread, the riskier the corporate bond. A period of widening (increase in the spread) reflects an increase in this perceived credit riskiness.

Funded status is a measure of the difference between the fair value of a plan’s assets and its benefit obligation.

Information ratio measures the risk-adjusted return of an investment relative to a benchmark. It is calculated by dividing an investment’s excess return (the amount by which the investment led or lagged the benchmark) by its tracking error. The higher the number, the greater the risk-adjusted relative return.

Maximum drawdown is a measure of downside risk over a given time period; it is the maximum loss from the highest point to lowest point of portfolio returns before a new high point is reached.

Tracking error is the standard deviation of the difference between the returns of an investment and its benchmark over time.

Our latest insights

-

Defined Contribution

-

Defined Benefit

-

Defined Benefit

-

Regulation & Legislation

-

Defined Contribution

Bloomberg® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Bloomberg’s licensors approves or endorses this material, or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

Bloomberg U.S. Long Credit Index is a market-value weighted index that tracks the total return results of publicly issued U.S. corporate and specified foreign debentures and secured notes that meet the specified maturity, liquidity, and quality requirements, with maturities of 10 years or more. To qualify, a bond must be SEC-registered and must be an investment-grade security. This index is unmanaged, and its results include reinvested distributions but do not reflect the effect of sales charges, account fees, expenses or U.S. federal income taxes.

The S&P 500 Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index based on the results of approximately 500 widely held common stocks. The index is unmanaged, and its results include reinvested dividends and/or distributions but do not reflect the effect of sales charges, commissions, account fees, expenses or U.S. federal income taxes.

The S&P 500 Index is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for use by Capital Group. Copyright © 2024 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution or reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC.